ARTA classics

Total time - 77:41

-

Sonata for Flute and Fortepiano, D major, op. 103 29:03

- Lento. Allegro non troppo 12:06

- Lento 8:32

- Finale. Allegro vivace 8:18

-

Four Fugues for Fortepiano

- Molto moderato, F minor (on a theme by Joseph Haydn) 4:14

- Maestoso. Presto ma non tropo, D minor (on a theme by Girolamo Frescobaldi) 6:19

- Allegro moderato, G minor (on a theme by Domenico Scarlatti) 4:06

- Allegretto vivo, A major 3:21

-

Sonata for Flute and Fortepiano, G major, op. 54 30:02

- Allegro 18:01

- Largo ma non troppo 5:46

- Finale. Allegro vivace 6:02

Yoshimi Oshima - twenty-four-carat gold flute by Muramatsu & Sankyo

Jaroslav Tuma - fortepiano by Paul McNulty, Divisov 1999, after Walter Sohn c. 1805

Is the Century of the Flute Really Over?

In the eighteenth century the flute was a highly popular solo instrument in chamber music and concertos. In fact, for a long time it was without competition in this respect, and the period truly was the Golden Age of the Flute. The more the flute gained ground as an instrument in the orchestra, eventually acquiring a firm position as the arrangement of instruments became increasingly standardized, it seemed to be lose its attraction as a solo and chamber instrument.

Certainly one reason for this was that the flute had not quite been perfected as an instrument — the strength of its tone as the instrument was constructed in those days was not particularly suited to the new demands being made on solo instruments. A more influential factor in shaping the flute repertoire, however, was that the flute was a favourite instrument of amateurs. The best known non-professional flautist of the eighteenth century was probably Friedrich II, for whom virtuoso concertos and sonatas were written. In Paris at that time compositions played by the foremost musicians in the royal chambers were published. By contrast, in the nineteenth century the needs of amateur flautists were met by music for the salon, arrangements of opera pieces, and variations on widely known melodies. To a large extent even difficult compositions by virtuosos on the flute, written mostly for their own concerts, were similarly intended.

At the turning point between these two periods there lived and worked Antonin Rejcha, a composer, flautist, and important music theoretician and educationalist. He was born in Prague in 1770, but lived most of his life abroad, as one of a number of Czech composers who had emigrated and worked in Europe's centres of music. Unlike most of them, however, Rejcha had left his homeland as a little boy. The adventurous ups and downs of his departure from Bohemia are known to us from his autobiography, which he dictated to his daughter Antoinette, in Paris, and whose manuscript has survived to this day.

Particularly responsible for Antonin Rejcha's career in music was his uncle, Josef Rejcha, a cellist, composer, and Kapellmeister, with whom the young Antonin grew up and studied music. In 1785 Josef Rejcha became Kapellmeister at the court in Bonn, and Antonin played flute and violin there. His friendship with his fellow-musician and contemporary, Ludwig van Beethoven, was particularly fruitful for him. Both men also studied with the organist Christian Gottlob Neefe at the recently established University of Bonn.

After his successful beginning as a composer in Bonn, Rejcha's career took him, by way of Hamburg and Paris, to Vienna. There he became acquainted with Joseph Haydn and a number of other prominent composers. In Vienna Rejcha continued to discover new possibilities in composition, which he had already begun to contemplate in Hamburg. A particular subject of interest to him was the fugue. He summarized his innovative principles in a collection of pieces for piano titled 36 Fugues Based on a New System. It contains uncommon time-signatures and rhythms, motifs, and modulations unusual for the fugue, breaking perhaps all the formal rules and conventions that had been handed down from the Late Baroque. Rejcha also demonstrated in this period a strong desire to write about music, presenting his views on theory and various other opinions in book form. He explained his new principles of the fugue in a short work which was the precursor to his later large theoretical works. It was probably back then that the Sonata in G Minor for Piano and Flute was written (later published in Leipzig as Op. 54, 1804/5).

In Vienna, which was then occupied by Napoleon's troops, there were few opportunities for artists, and Rejcha moved on, first to Leipzig, and then suddenly to Paris by way of Prague. In Paris, where he spent the rest of his life, Rejcha established himself as an outstanding educator, particularly after 1818, when he was appointed teacher of counterpoint and the fugue at the Paris Conservatory. Many of his students went on to make their mark as great composers, for instance, Liszt, Berlioz, Flotow, Gounod, and Franck. Rejcha's theoretical writing also had a great influence.

As a composer of opera, the leading genre of his day, Rejcha was, however, unsuccessful. His chamber works were far more important. With his natural tendency to experiment and discover new paths, it was in chamber music that Rejcha found fertile ground. Of the many possible instrument combinations he tried in his music, perhaps the most successful was the wind quintet. Actually, with his 24 wind quintets Rejcha is the founder of this kind of music, and himself thought highly of these works of his. The Grand Duo in D Major, Op. 103, for flute and piano was also written in Paris, probably in c. 1820 (and published in Paris in 1824).

‘Once while playing a symphony we came to the fermata, and I used it for a twenty or thirty-bar improvisation. When we next performed that symphony the orchestra refused to continue unless I played the new improvisation. I had to do this each and every time we played, which was very often', said Rejcha in his autobiography, recalling his youth in Bonn. Although he later ceased to play as a professional flautist, he wrote a number of chamber works for the instrument.

Antonin Rejcha died in Paris in 1836. The flute had to wait for more than half a century before it was again noticed, this time by the French impressionists. It is somehow symbolic that the first among them was Debussy, a pupil of Franck, who had studied under Rejcha at the age of thirteen.

Vaclav Kapsa

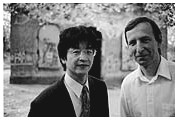

The outstanding solo flautist Yoshimi Oshima is a representative of the bold entry of Japanese wind players on to the international stage of interpreters of Classical music. He was born in Osaka (1958), and graduated in music at Kyoto (1981) as one of the most talented young flautists there. In the years 1981-4 he attended post-graduate classes at the Hochschule fur Musik, Vienna, under Wolfgang Schulz, a flautist of the Wiener Philharmoniker. Oshima has received a number of international awards, including First Prize at the UFAM, Paris, a special prize at the Maria Canals Competition, Barcelona, and many prestigious Japanese competitions.

From 1987 to 1990 Yoshimi Oshima spent three years in Prague as first flute of the Czech Radio Symphony Orchestra. Upon returning to Japan he took up an equally important seat in the Gunma Symphony Orchestra. In 1990 his career as a successful soloist of all the important Japanese concert halls began. From that time onwards he has also been invited every year to perform in Europe. He has played in Vienna, London, Prague, Brno, and Pilsen, including at a number of festivals, for instance the Prague Spring (1998). Oshima has collaborated with Wolfgang Schulz, Peter Schmiedl, Michala Petri, Josef Suk, Bohdan Warchal, Shizuka Ishikawa, Josef Hala, the Dolezal Quartet, the Prazak Quartet, the Kocian Quartet, the Slovak Chamber Orchestra, the Suk Chamber Orchestra, the Virtuosi di Praga, the Prague Symphony Orchestra FOK, the Janacek Philharmonic, and many others.

Of his CD recordings, particularly Mozart's concertos for flute and flute sonatas by Bach and Haendel (recorded with harpsichordist Jaroslav Tuma) merit special mention. Some of his concerts have also been broadcast on radio and television. His playing is highly valued particularly for the 'warm, human atmosphere' it creates. In 1997 Yoshimi Oshima was appointed Professor at the Music Faculty, Kyoto City University of Arts.

Organist, harpsichordist, clavichordist, and, lately, also a player of the pianoforte, as well as improviser, composer, and teacher, Jaroslav Tuma was born in Prague (1956). He graduated from AMU, Prague, where he studied organ with Milan Slechta and harpsichord with Zuzana Ruzickova. While a student he won a number of prizes in international competitions, including for organ interpretation in Linz, Prague, and Leipzig, and for improvisation on the organ in Nuremberg (1980) and Haarlem (1986). He has played at many festivals (the Prague Spring, International Organ Week, Nuremberg, the Dresden Music Festival, and the Flanders Festival), and today he sometimes sits on the jury at competitions. Since 1990 he has been teaching at AMU. As a solo interpreter Jaroslav Tuma devotes himself to Renaissance, Baroque, and early Classical music. He enjoys giving concerts on period instruments (or copies), but at his concerts he also likes to introduce twentieth-century music. His travelogue includes the names of most European countries, and he has also given concerts and lectured in the USA, Japan, Singapore, and China. In Prague in the early 1990s he recorded the whole of Bach's works for organ. He records for radio, television, and many record companies.

Jaroslav Tuma can be heard on ARTA Records with Meinhart Niedermayr, playing Mozart's sonatas for flute and harpsichord (F10023), Frantisek Benda's sonatas for violin and continuo with Ivan Zenaty (F10022), and on the composition for harpsichord, Zoe (F10054), on a recording of selected compositions by Jan Jirasek. Tuma's unique project, Organ Improvisation (F10064), and the world premiere of Johann Sebastian Bach's Inventions and Symphonies, using a period clavichord (F10076), are especially notable.

An encounter with a period fortepiano (or rather a masterly reproduction of one) on a recording of Tomasek's Eclogues (F10086) was the logical continuation in the evolution of Jaroslav Tuma's art of interpretation, and the chronological expansion of the number of historical keyboard instruments he has played.